| HOME | THE MAN | THE HOUSE | TIMELINE | DIRECTIONS | CONTACT |

A Historical Tribute

1244 S. Sixth St. - 20081244 Sixth Street

Old Louisville - The Neighborhood

A Brief History of Old Louisville

The neighborhood known as Old Louisville is approximately 1200 acres, or 48 square blocks, 2 miles south of the Ohio River and the city’s central business district, containing three National Historic Preservation Districts and such a diversity of persons and activities that it constitutes a city within a city community. What was once Louisville’s first subdivision, this urban neighborhood, later known as Old Louisville, experienced a physical decline that has been reversed in the past few decades by urban gentrification, and attracts visittors because of its historical and architectural significance, its geographical proximity to the business and government center of Louisville, and its inviting community spirit.

Development of the area originally known as the Southern Extension began in the 1830s. The earliest homes in the neighborhood were country residences. North-south avenues were extended across Broadway from the city proper in the 1850s, and mule-drawn carts were extended out Fourth Street to Oak by 1865.

The Southern Exposition of 1883

In 1868, the city’s boundaries were extended south to the present site of the University of Louisville’s Belknap Campus, thus formally incorporating the area into the city limits.

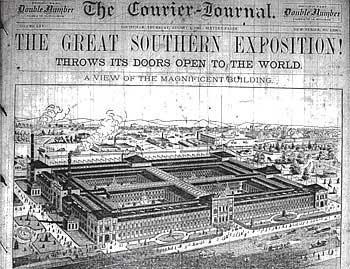

The Southern Exposition

Following the Civil War, Louisville experienced a tremendous surge of growth and prosperity. In the area now known as Old Louisville, the single most dramatic stimulus for expansion was the Southern Exposition of 1883. The exposition’s main exhibit hall covered the area between what is now Magnolia Avenue (formerly Victoria Place) and Hill from Fourth to Sixth Streets, a single enclosure 900 by 600 feet. After the Southern Exposition ended in 1887 the Victoria Land Company bought the vacated property and built St. James, Belgravia, and Fountain Courts.

The Southern Exposition served as a catalyst for development in the surrounding area. In 1885, 260 homes valued at an average cost of $6,150, or $1.6 million dollars, was constructed between Kentucky and Magnolia Streets. The most popular Victorian style houses built were the Queen Anne and the Richardsonian Romanesque. On March 1887, the Courier-Journal declared Louisville the “New Gotham” and hailed that the city had the most beautiful homes.

Historic Preservation District

1416 S. Third Street

Old Louisville is the largest Victorian Preservation District in the U.S., and the 3rd largest Historic Preservation District in the U.S. Several aspects of Old Louisville architecture are significant. First, a variety of styles ranging from the formal, symmetrical designs of Renaissance Revival to the romance of Queen Anne and Chateauesque, can be viewed within a one or two block area. Second, a diversity of colors, materials and scale abound in the residences here. Limestone and brick were readily available in this area where timber was a promenent building material in the eastern seaboard cities at the time. Three-story homes along Third and Fourth Streets are the largest and most elaborate, followed by those in St. James Court, Ormsby Avenue, and Second Street.

Moving farther west and east, the houses become smaller and less elaborate. Along Sixth Street to the west, and Brook and Floyd Streets to the east, one and two story frame houses begin to replace the large limestone and brick residences. Smaller row houses can also be seen in Old Louisville, including a number of carriage houses converted to residences. A variety of dwelling types, including some early experiments in apartment buildings and duplexes, can also be seen. Servicemen returning home after

St. James Court Art Show World War II created a demand for housing, and many large homes were converted to apartment buildings. As the suburbs flourished in the years after the war, the neighborhood became almost abandoned. Urban gentrification during the late 20th century began to reverse the decline and decay of the neighborhood.

As you walk through Old Louisville, notice many buildings contain bits and pieces from several architectural styles. This eclecticism makes Old Louisville very picturesque. The houses are meant to evoke an emotional response from the viewer and are best appreciated from the sidewalk rather than a drive-by down the street. Houses in Old Louisville are not lifeless museum pieces, but rather homes and offices of people living and working in a thriving neighborhood.

| HOME | THE MAN | THE HOUSE | TIMELINE | DIRECTIONS | CONTACT |